Up Next

Shirley Dauger went to Paris for adventure. She made a family and career.

The multi-faceted American, who came to France ‘to smell the roses,’ became a mother, breast cancer survivor and successful private driver

Black Americans in France is an ongoing series highlighting African Americans living abroad during the 2024 Paris Games.

“I actually came here to explore. When I was in college my professor said, ‘The world is your oyster.’ So, I took that and ran with it.” – Shirley Dauger

When Shirley Dauger decided to move from Long Island, New York, to Paris, she made it clear that she was not making a protest move. She was making a move for adventure.

“I didn’t leave, I went to explore,” Dauger said from her home in Paris. “I’m not trying to run away because I’m feeling persecuted. I wanted to know the world.”

As the daughter of parents who immigrated to the United States from Haiti, Dauger appreciated that it was possible to leave your country and love your country.

“They left their country for a better life, but they loved their country,” she said, “They always loved their country, but they knew they had to leave to have a better life, but in no way did they ever talk badly or poorly about their life in Haiti. They wanted more economic opportunities so they came to America. But my parents were very Haitian. They talked about Haiti always in a wonderful light.”

In the 30 years that she has lived in France, Dauger’s life has taken a number of intriguing twists and turns. She has invented and reinvented herself, from being a career nurse, to a singer and finally establishing her own private transportation company, My Pearls of Paris.

“I was free to explore. That’s what being in Europe, or another country allows you to do,” Dauger said. “It frees you from all those stereotypical limitations that sometimes people place on you coming from where you we’re born. You come here and all of a sudden you have access to things you never had before.”

Born in Brooklyn, and raised in Baldwin, Long Island, Dauger took her first trip to Paris with a friend in 1990, a year after graduating from Molloy University with a bachelor’s degree in nursing.

As recent employees of Winthrop University Hospital, the two friends had money. “We were always talking about traveling and wanting to see the world,” she said. “So, we flew into England, then France, then Germany, then to Italy. In Italy, we worked in Venice, Rome, and Florence.”

She loved Paris so much she returned six months after the first trip.

“We came back six months later to France because we loved it so much,” Dauger said. “You know how on tours you don’t get to really see a lot, you get a little taste. But we wanted to come and really get to know the city. So, we came back for 10 days. We loved Paris. Because Paris — especially for us, for Haitians — Paris meant more to us because of the link with Haiti, because Haiti was a French colony.’’

When Dauger returned to Paris in 1991, it was basically to pursue a love interest who she had met during her first trip to Paris. They began dating.

The romantic relationship took her back to Paris several times between 1990 and 1991. During her visits, Dugar became fascinated with the international scene and with meeting so many African Americans who had relocated to France.

“This is new for me. I didn’t know any ex-pats,” she said. “I knew of people leaving countries coming to the United States, but I had never met anybody who left the United States to go abroad. Now I’m meeting them. Some were working for corporations, some moved for a change of scenery. I’m meeting writers, I’m meeting people who moved for different reasons. I thought it was fascinating. I was like, ‘Wow, why didn’t anybody tell me that the international theme was really interesting?’ Had I known, instead of becoming a nurse I may have worked for the UN.”

Dugar decided that she wanted to relocate and that her nursing degree might be her ticket of passage. “I said to myself, ‘Wait a minute, I’m a nurse. Could my nursing degree work here?’ she said. “I started looking into that. I thought, ‘doesn’t a French heart work like an American heart?’ ”

Dauger made it happen. In 1992, she enrolled in the IFSI nursing school in Versailles. She lived with her French boyfriend and embraced the adventure.

“I’m living in France now, and this is cool,” she said. “From October of 1992 to June of 1993, I am living in Versailles, but in the Paris region. So, I’m living life. I’m traveling, seeing different parts, and getting to master the French, master the culture, master asking for things, buying food. I’m literally living as a French person and going to school.”

While she was in the French nursing school, Dauger did a one-week rotation at the American hospital in France. She knew that’s where she wanted to work. She applied for a position after she earned her degree and passed her boards.

Having a degree was one thing, securing a work permit was something else entirely, especially at a time when jobs were scarce. With no job immediately available, Dauger returned to Long Island and her job at Winthrop Hospital in 1993. To her disappointment, Dauger learned that she did not get the position at the American hospital. Her work permit was denied.

There was one more alternative, and she took it: “In France, there’s not many ways to get work permit, but one of the major ways of getting work permit is to marry.”

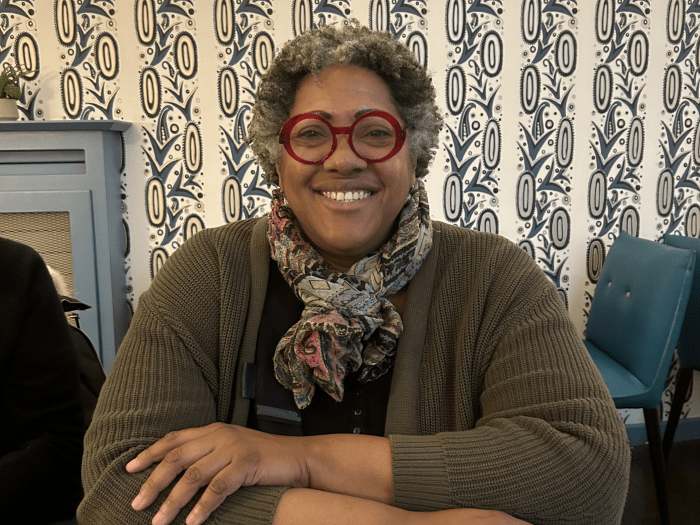

Shirley Dauger

In 1994, at a ceremony in Versailles, Dugar and her French boyfriend were married. She began working in the Coronary Care Unit of the American hospital a year later on Feb. 20, 1995.

Six years later, Dauger and her husband divorced, and a new chapter of her life began: She was on her own for the first time in her life, a single Black American woman in Paris.

“I finally got my very, first apartment because I left home and went to live with him,” she said referring to her former husband. “So, I never lived by myself.”

She began to broaden her horizons beyond nursing. She took voice lessons, began to sing with choirs, ensembles, bands. Singing became a hobby that she took seriously even as she continued to work at the hospital.

“I start singing, and I’m with other people sharing the love of music. I am living the life,” Dauger said. “I started up with an opera company, I’m singing opera, I’m singing Negro spirituals, gospel. I’m singing arias. I’m singing in Italian. I’m singing in German. I’m singing in all these different languages. I’m doing jazz and I’m enjoying the heck out of myself.”

She became known in certain circles, not as a nurse, but as a U.S.-born singer. That was a special designation, one with historic roots attached to Black American entertainers who had come to Paris for centuries. “All of a sudden you become an ambassador, the fact that you are an American, you become this ambassador, and people are asking you questions left and right, about the United States.

“They’re asking me, ‘Where did you come from? Why did you leave? Where did you used to live? Did you use to live in a hot neighborhood?’ ”

Dauger began to explore the rich history of African Americans who came to Paris, often alone, often to escape white racism. While this was not her reason for relocating, she embraced the adventurous spirit of those Black ex-pats. She became inspired by Josephine Baker, who came to Paris at age 19 and became one of the greatest entertainers of her era.

“When you think of it, Josephine Baker came here by herself, she was often the only Black person. She had a purpose in life,” Dauger said. “At the time I came here, I was looking for my purpose in life. I’m a nurse, yes, but is nursing the only thing that defines you? I don’t want to be just defined by one thing. I think we have lots of talent, and I wanted to explore. I was free to explore that.”

When a friend created a new band with two other musicians, she recruited Dauger to be the band’s singer. The band formed two years later. “And that’s how I met my second husband,” she said. Her soon-to-be-husband was the band’s bass player.

The relationship evolved quickly. They began dating, moved in together and in 2009 they were married. In 2010, Dauger had the couple’s son.

It was at this point that fate threw a curve ball. Shortly after the birth of her son doctors discovered that Dauger had a tumor in her leg. She had an operation and was on the road to recovery. “Everything is fine. I get back on my feet, and this whole time I’m on maternity leave,” she said.

“Then I feel a lump in my right breast.” She was diagnosed with Stage 3 breast cancer. Her son was 10 months old at the time of her diagnosis. “I go from maternity leave to sick leave,” she said.

Shirley Dauger

Through rounds of chemotherapy and radiation therapy, Dauger chose to see the glass as half full. “And so, during that whole time, it allowed me to be home. If you want to see the bright side of a fearful moment, I was able to be home with him, see him grow, and still be able to have my salary,” she said.

Dugar was too weak to go back to full-time nursing, though she was able to secure a desk job working in quality assurance. The job was part-time and that meant part-time money. She needed to supplement her income.

“And so, my husband says, ‘Well, have you ever thought of doing a little bit of Uber?’ ” Dauger said. “I’ve always loved to drive. If I go out with friends, I’ll be the one dropping my friends off at their home at night. And my husband’s like, ‘Well, why don’t you get paid for it?’ “

By mid-2017, Dugar began driving Uber on a part-time basis. She loved the job. “I’m driving and I’m loving it. I’m talking to people. I’m meeting people from all over the world. My English comes in real handy, because a lot of English-speaking people don’t know French well enough to converse. And a lot of French drivers can’t speak well enough to converse, either, in English. And since I’m a nurse, I know how to take care of people. I know how to help people. I know how to assist people. I know how to listen to people.”

Through word-of-mouth, passengers began asking if Dauger drove privately. Could they call on her directly?

“Little by little, I was noticing a need for an English-speaking driver. And at the same time, people wanted to ask me questions like, ‘Shirley, where do I go? Where’s the best place to eat?’ Or they would comment, ‘What neighborhoods should I go to?’ And people want to know where the Black neighborhoods were,” she said. “And so Chinese people want to know where the Chinatown is. Mexicans want to know where the Mexicans were. Everybody wants to know where their people are. And little by little, I was able to show them and let them know where the hoods were.”

Driving also gave her time to take care of her special-needs son. She determined that she did not want to go back to the hospital.

“I said to myself, I don’t want to be stuck in a hospital,” she said. “If I went back to nursing, [I’m] stuck for 12 hours. I need to have that flexibility. Driving would be one of the best ways to give you that flexibility. I love driving. Driving is my blood.”

A good friend, Ricky Stevenson, owner of Black Paris Tours, helped by giving Dauger referrals.

“She would often call me to handle a couple of her clients,” Dauger said. “And then little by little, she said, ‘Hey Shirley, I think it would be a great idea if I have your information and people could call on you directly.’

“And that’s where I started getting the idea of maybe there’s a real need for English-speaking drivers, but then they’re also Black American drivers. People feel very comfortable. They feel at-ease. Little by little, I said, I think there’s a real need here and I think this could really turn into something.”

She has grown the business over the last four years, building a robust private clientele. At age 57, with a son a husband and her business, Dauger is comfortable with the life she’s living.

The adventure that drew her to Paris 30 years ago has mellowed into a way of life.

“I came to France because I wanted to smell the roses. I wanted to know what it felt like to live and not to survive,” she said. “Coming to France, I learned how to slow down. So I come here and I’m learning to literally take my time. In the United States, you’re always going a mile a minute. You got this, you got that. You got the to-do list. You are hustling from morning to night. And people look at you. If you’re not doing a hundred million things, they’re looking at you like, ‘Oh, you’re not productive.’

“Whereas in France if you do three things, ‘Oh, you’re highly productive.’ So that’s why French culture is known for the art of living. When clients come from the United States, they have a whole list, ‘Oh, we want to do this, we want to do that.’ And I look at them and I say, ‘But when are you going to have that experience? When are you going to enjoy the French experience of being here?’ “

As she grows her business, Dauger continues to sing. She is a member of a choir and part of an opera company. “We’re putting on plays, in Paris. Little theaters, little venues, but we’re doing it,” she said.

“For me, being here is understanding that there is another way of living. We don’t have to be like a chicken running around without its head. People ask me, ‘What are you doing here?’ And my answer all the time is, ‘I’m living the life. I’m living the life.’”