Up Next

Novelist Jake Lamar followed his Black writing role models to France

The Harvard graduate became a part of the literary tradition of Black American authors living in Paris

Black Americans in France is an ongoing series highlighting African Americans living abroad during the 2024 Paris Games.

PARIS — “There are three types of Black folk living in Paris,” novelist Jake Lamar told me recently when we met at a cafe near his home in Montmartre.

Lamar, 63, became part of a long rich literary tradition of African American writers in Paris when he moved here in 1993. He settled in the Montmartre district, one of the earliest Black American enclaves in Paris. The French capital has been a magnet for African Americans since the turn of the 20th century. How they have adapted to life in the City of Light has varied.

“There’s one type of American who wants Paris to be just like home and they only hang out with other Americans. They only speak English. They complain about the French all the time, but they like it here. But it’s like mentally, they’ve never left the states,” Lamar said.

The second type of Black expat “just disappears into France,” Lamar said. “They married a French person and just disappeared into France. They didn’t want to hang out with Americans, Black or white. They only spoke French. They often had French kids they spoke to. They worked in a French environment. They just rejected ties to America.”

Lamar counts himself among the third type: the betwixt and between Black expat. “We love being here and will integrate to a certain point, learn the language make a living. But we also remain very strongly tied to America and love hanging out with other Americans because Americans in general are easier to deal with here than in America, Black Americans who made a kind of unusual choice. A lot of us didn’t quite fit in in America. But we weren’t ready to totally reject America and become French — we liked the dual consciousness.”

Despite living in Paris for three decades, Lamar has resisted certain aspects of French culture, just as there are elements of United States culture he will never forsake.

“I’m never going to be a big soccer fan, that’s not going to happen,” he said. “I’ll watch the World Cup and the Euro [European Championships], but I’m just not going to sit down and watch any PSG [Paris Saint-Germain] match. But I’ll watch any NBA game or any NFL game.”

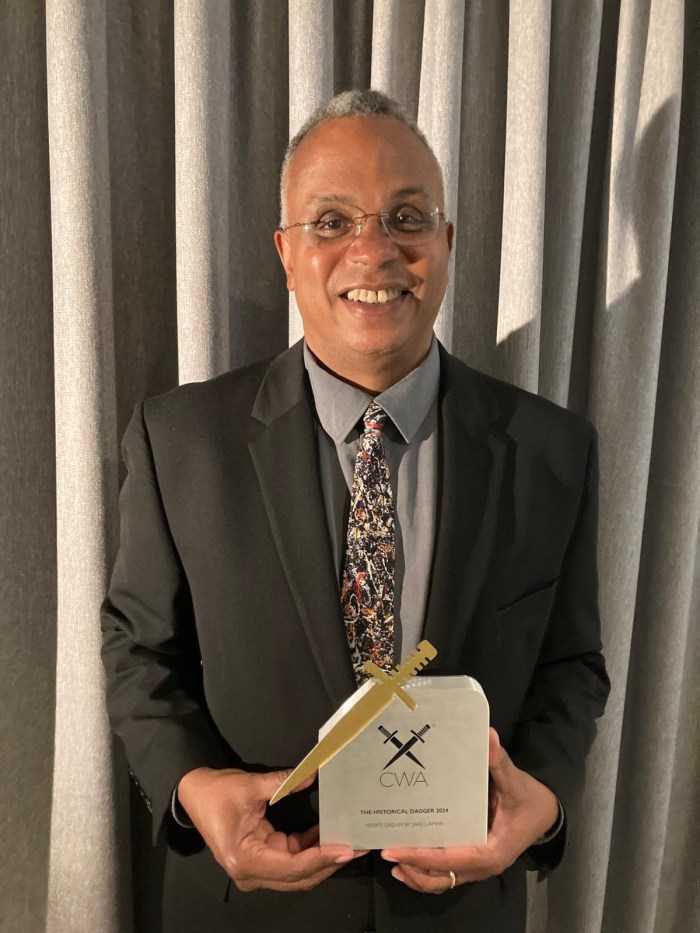

Earlier this month Lamar won the prestigious Dagger Award for crime fiction in the historical novel category for his latest novel “Viper’s Dream.” The award put Lamar in the tradition of Richard Wright and James Baldwin but even more squarely in the tradition of Chester Himes, whose Harlem based detective novels were first published to great acclaim in France.

More significantly, the award, the recognition and Lamar’s consistent outpouring of work puts him in the larger literary tradition of Black American writers who have sought refuge and escape in Paris for more than 100 years.

Ulf Andersen/Getty Images

Lamar was born in the Bronx, New York, and attended Harvard where he majored in history and literature. His first job out of college was with TIME magazine, though when I asked how he made transition from journalist to novelist, Lamar said that being a journalist was never a goal nor an aspiration.

He knew about Black literary tradition in Paris and wanted to become part of it. Lamar wanted to be a writer; specifically, he wanted to be an African American writer living in Paris.

“I started out wanting to be a novelist,” he said. “From the time I read Baldwin and Wright and [Ralph] Ellison and all these great writers when I was in high school, I wanted to be a fiction writer.”

When he was 13 years old, Lamar said that four works changed the course of his life: “The Bluest Eyes,” Toni Morrison’s debut novel; “A Raisin in the Sun,” the iconic play by Lorraine Hansberry; “Black Boy,” Wright’s memoir about growing up in Mississippi; and “Go Tell it On The Mountain,” Baldwin’s autobiographical first novel.

“I was so moved by this book, and I asked my teacher, ‘Who is James Baldwin?’ and he said he was American living in Paris. That seemed like an exotic idea,” Lamar said. “It must have been a little while later that I read “Black Boy,” and I found out that Richard Wright lived in Paris. That was starting to seem like a pattern.”

When he worked at TIME, Lamar hired an agent who suggested that for his first book project Lamar consider writing a memoir although he was only 28 years old at the time. The memoir became “Bourgeois Blues.” Although the memoir was about the strained relationship between Lamar and his father, the book exams the evolution of racial politics in the United States.

He began the book when he was 28, the memoir was published two years later in 1991. When he won the prestigious Lyndhurst Prize the same year, Lamar quit TIME and began laying the foundation to move to Paris. He used the first check to get out of debt, the second check to pay off his college loans. He made the final payment in 1993; the next day he was on a plane to Paris.

“It was always Paris,” Lamar said. “I didn’t want to go to London. I didn’t want to go to Spain. It was Paris and that literary tradition.”

The idea was to stay for a year, “That seemed reasonable. I thought I would have to go back to the States it was gonna be like my last wild adventure before I settled into a teaching job somewhere and then be became a respectable grown up. I’m just going to have this adventure for a year while I work on this novel, because I had the contract for the second book.”

The longer Lamar stayed in Paris, the longer he wanted to stay. He met older writers like Ted Joans and James Emanuel who showed him how to thrive and introduced him to the Black literary community.

“They were links to this history that I that I loved,” he said. “What I learned from men like Ted Joans and James Emanuel was that you could live improvisationally that if you were willing to risk it, you didn’t have to live a standard paycheck to paycheck salaried life. You could dare to deliver improvisationally that was what took courage. But the thing is I loved it so much and was meeting such great people and that was the inspiration to stay.”

Jake Lamar

Lamar was actually in line back in the United States for a job at Carnegie Mellon teaching creative writing. “And then I met the woman I was going to marry. She was European. she’s an actress and singer and there was nothing for her in America. I was loving it here and I thought ‘OK I’m just going to try it I’m just going to keep winging it. We’re still together so it worked out,’ ” Lamar said.

His decision to move to Paris was rooted in following a literary tradition. The move was not a protest vote against the United States, though there was much to protest against.

“I did not come here to protest,” he said. “But that said, right before I won this grant in 1992 was the verdict in the Rodney King police brutality and the whole uprising in L.A. Then I got this grant and a year later I was gone. I never said to myself, ‘Oh, because of what happened in L.A. I want to get out.’ I wanted to see how things work somewhere else, you know? There was that curiosity. I didn’t find my life in America intolerable, but I was curious.”

Four months after arriving in Paris, Lamar and another Black friend were stopped by Paris police as they were walking back from a gathering through an upscale French neighborhood. Lamar was calm, though his friend lost his cool and fought back.

That was something Lamar knew he could have never survived in the United States.

“That could have happened in America,” he said. “The only differences are that in America, this guy would have probably been shot once he stared fighting the police. They would have shot him and then killed me as a witness.

“It made me realize that whatever anybody will tell you France is not a racial paradise, and I was very happy to get that lesson after four months here rather than going four years thinking, “Hey, everything’s wonderful, everything’s great.”

While there is no earthly paradise for Black Americans, Lamar feels a certain weight has been lifted off his shoulders here. It’s a weight he never knew existed until he left.

“I’ve never felt the kind of daily grind of racism and some attitudes that you get in America,” he said. “I don’t go back much anymore, but I would go back and just go ask for help at the information desk, and there’ll be a white person talking to me in a sneering tone, and I wasn’t used to it anymore. I’m used to being calling Monsieur and being treated with respect. And I go into a shop and the security guards follows me around. I feel it right away. It’s like, ‘Oh, God, I forgot about and this.’ The longer I stayed over here, the more difficult it was for me. If you live in America, you don’t realize, like a fish doesn’t know it’s swimming in water until you throw him out of it.

“I just thought, ‘This is the way it is,’ and then you go someplace else and people are just different. I mean, certainly French people aren’t always nice, but you don’t get that immediate feeling of distrust or suspicion or condescension.’’

As with other Black Americans expats, I wondered how Lamar saw himself. He said his identity was similar to how he saw himself in the United States.

“Someone pointed out to me years ago that when people ask me where I’m from, I don’t say America, I say New York. It’s the same with Paris,’’ Lamar said. “I’ve traveled all over France, but I’ve lived in this one arrondissement for almost half my life. I know my way around Paris. I know the customs in Paris. I care about what happens in the city passionately.

“I don’t feel French, but I do feel Parisian.’’