Up Next

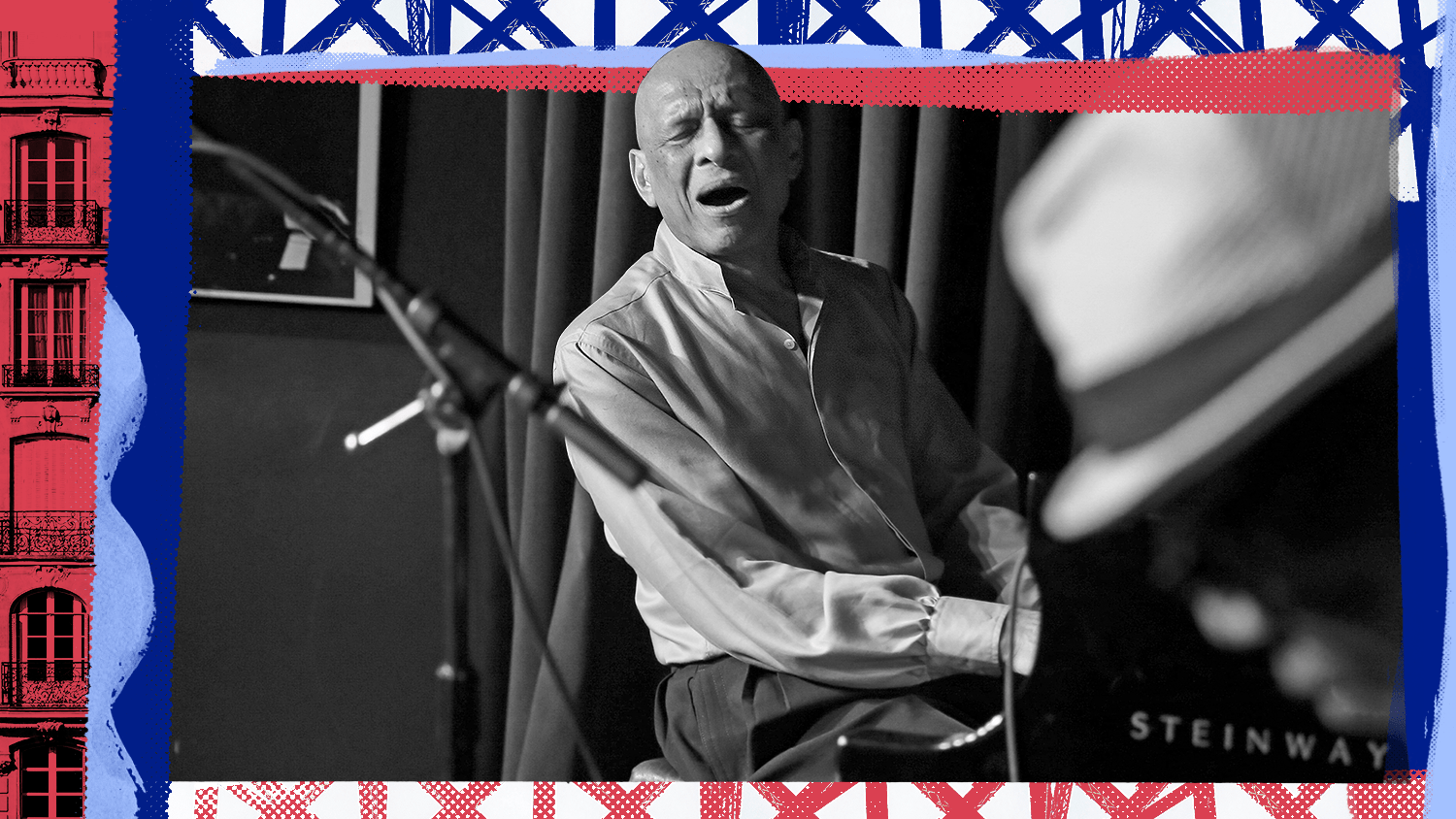

Jazz pianist Kirk Lightsey found respect in Paris that was missing in the United States

The 87-year-old moved to Paris for good in 1994: ‘Living in Paris was very easy’

Black Americans in France is an ongoing series highlighting African Americans living abroad during the 2024 Paris Games.

Pianist Kirk Lightsey moved to Paris for good in 1994. When he relocated, Lightsey, 87, became part of the latest wave of African Americans to relocate to the City of Lights.

Since the early 20th century, Paris had been a welcoming magnet for African Americans who saw the country and the city as a haven from the harsh realities of racism in the United States. For generations of Black Americans, Paris presented possibilities, fresh starts, and an escape from the constant drone of racism.

As a celebrated jazz musician, Lightsey also became part of a rich jazz tradition that had intoxicated Parisians since the beginning of the 20th century when jazz was introduced by regimental bands of Black American soldiers who spread the exciting new music across France.

While Paris was by no means a racial paradise, for waves of African writers, musicians and artists, the city offered a safe space where their humanity was not only seen but valued.

“Paris was welcoming,” Lightsey said from his home in Paris during a recent interview. “I felt freer. I felt appreciated. I felt like people were people, and I was just a person to all the people, and I was very appreciated. Being here has been wonderful. It’s been great.”

Brian O’Connor/Images of Jazz/Heritage Images via Getty Images

Born and raised in Detroit, Lightsey began playing piano at age 5 and spent his teenage and early adult years becoming part of the city’s vibrant jazz scene. Ultimately what pushed Lightsey to relocate to Paris was that the weight of racism became too heavy to bear.

The first event occurred when he was serving in the Army.

Lightsey was drafted in 1960 and was a member of the Fort Knox Army Band. During one visit, Lightsey and his then-wife decided to go outside of the base for dinner.

“She was visiting me at Fort Knox. We were starving. We just drove down the hill about 15 minutes from Fort Knox,” he recalled. “I said, ‘I’ve never been to this place, but it looks pretty good, so let’s go in there and get some food.’ We walked in, I had on my uniform and they immediately said, ‘I’m sorry, we don’t serve Black people in here.’ I did not know what to do. The only thing I could do was take Shirley by the hand and walk out. That was just the most outrageous thing that’s ever happened to me as far as racial issues are concerned. And I’m still expected to fight for my country.”

Besides soldiers, Black musicians were not spared the ignominy of racism as they toured.

“Count Basie’s whole band had to do that, many people who were on the road, all these Black musicians during that time had to go through this,” Lightsey said. “That’s why so many Black people who were playing music during this time chose to come to Europe, chose to come to Paris, and they stayed for the most part. They stayed because they knew when they went back to the States, they were going get kicked in the a– by white toes.

“There was no racial issue here [France]. The French people were really happy to accept us as artists and they held us in very high esteem.”

After being discharged, Lightsey became a staff pianist with Motown Records and continued to make his name playing with some of Detroit’s greatest musicians. In the mid-1960s, Lightsey joined trombonist Melba Liston’s all-female band and made the pilgrimage to New York.

After the job with Liston ended, Lightsey moved to California in 1969 to work with singer O.C. Smith. It was during this time that he made his first trip to Paris. He subsequently joined saxophonist Dexter Gordon’s band, returned to New York, and became a fixture on the New York jazz scene.

One evening, Lightsey was returning from a gig on a crowded subway when he was arrested by New York transit police on the nebulous charge of jostling. He later found out that he and other Black passengers had been racially profiled by transit police as part of a pattern that was uncovered when transit police targeted an off-duty Black police officer. Lightsey sued the city and won a healthy settlement after seven years.

“During that time, I was working all over New York and had visited Europe several times,” he recalled. “I played in Paris and Paris seemed like a good place to be.”

Lightsey decided to use the money from the settlement to move himself and his new wife, who was French, to Paris. At age 57, he had had enough.

The subway incident was simply the last straw.

“What was happening politically was a big part of why I left the States and came to Europe,” he said. “The club owners were dying, and things were changing in the business in New York, and it just wasn’t the same feeling. Now it’s even worse than then, but then it was bad enough. It was during a time when lots of American musicians were moving to Paris and to Europe because life in the States was just so ugly for Black Americans and especially Black American musicians. Lots of people moved over here. And I came over here and found lots of people that were friends of mine.”

Samuel Dietz/Redferns

There was no shortage of work for Lightsey, who by this time in his career enjoyed universal acclaim. He regularly worked in several clubs in Paris, the surrounding countryside and taught in an educational program outside of Paris. Lightsey believes his career rose to another level in Paris.

“Yeah, it did. It went to another level because now not only was I from New York and a player from New York, but that was a great level to be from,” he said. “And I was one of the top calls on the piano in Paris and in other parts of Europe that I’d been to. So, I was on a ladder going up.

“Living in Paris was very easy. I just had to learn the language. But that wasn’t so hard because people in Paris at that time were trying to learn English, so they would practice their English with me back and forth. I don’t need to speak French as much as I did when I first came here.”

Because of the historic lineage of Black jazz musicians in France, Lightsey said, he and other jazz musicians enjoy a level of respect often missing in the United States.

“My French wasn’t bad. It was beginner’s French, but when people would talk to me, they could tell that I wasn’t a French person or an African person, that I was from the U.S. And that gained respect from them,” he said. “To be here and be an American musician and to be a musician from the States and live in Paris was a great honor to them. So, I was greatly respected for being a musician and from the States. I was working all the time. So, it was a great feeling.”

As we ended our conversation I asked Lightsey what, on balance, he had gained from relocating to Paris. “You gain freedom,” he said. “You gain a language. You gain being close to very interesting places, like Germany. You’re close to Vienna, you’re close to other worlds. And that’s great because you can jump on a train and go anywhere.”

How does he see himself? As a Black Frenchman? A Black man living in Paris? “As an American living in Paris with a French family, my French wife and my French daughter,” he said.

Would Lightsey ever consider moving back to the United States?

“Never, even in my next life,” he said. “With what’s going on there politically, it’s nuts. It’s just going crazy.”